Nineteenth century London is the center of a vast British Empire, a teeming metropolis where steam-power is king and airships ply the skies, and where Queen Victoria presides over three quarters of the known world—including the east coast of America, following the failed revolution of 1775.

Young Gideon Smith has seen things that no green lad of Her Majesty’s dominion should ever experience. Through a series of incredible events Gideon has become the newest Hero of the Empire. But Gideon is a man with a mission, for the dreaded Texas pirate Louis Cockayne has stolen the mechanical clockwork girl Maria, along with a most fantastical weapon—a great brass dragon that was unearthed beneath ancient Egyptian soil. Maria is the only one who can pilot the beast, so Cockayne has taken girl and dragon off to points east.

Gideon and his intrepid band take to the skies and travel to the American colonies hot on Cockayne’s trail. Not only does Gideon want the machine back, he has fallen in love with Maria. Their journey will take them to the wilds of the lawless lands south of the American colonies—to free Texas, where the mad King of Steamtown rules with an iron fist (literally), where life is cheap and honor even cheaper.

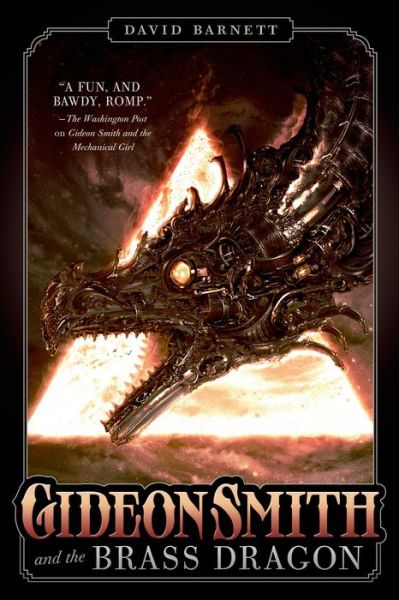

![]() David Barnett’s Gideon Smith and the Brass Dragon is a fantastical steampunk fable set against an alternate historical backdrop. Get it September 16th from Tor Books!

David Barnett’s Gideon Smith and the Brass Dragon is a fantastical steampunk fable set against an alternate historical backdrop. Get it September 16th from Tor Books!

1

The Lost World

Charles Darwin stood motionless at the mouth of the cave, his serge trousers pooled in a ragged heap around his ankles, as a shrieking pteranodon wheeled and soared in the blue morning sky.

“Good God, man!” said Stanford Rubicon, pushing away the crudely stitched-together palm fronds he had been using as a blanket. “How long have you been standing there like that?”

Kneading the sleep from his eyes, Rubicon clambered over the loose stones to where Darwin stood by the ashes of last night’s fire, taking a moment to glance out from the lip of the cave to the steaming jungle below. The sun had risen over the jagged claws of the mountains to the east; it was shaping up to be another beautiful day in hell. The pteranodon, drifting on the rising warmth, cawed at Rubicon and glided out of sight. Darwin’s rheumy eyes swiveled in their sockets toward Rubicon, filled with pain and humiliation. He tried to speak but succeeded only in dribbling down his long beard.

“There, there, old chap, don’t fret,” murmured Rubicon, pulling up Darwin’s trousers without fuss or ceremony. “Soon have you mobile again.”

Using the makeshift shovel, little more than a piece of curved bark tied with twine to a short stick, Rubicon gathered up a few pieces of their dwindling coal supply. There was only enough for three days, perhaps four, and that was if they didn’t use it on their cooking fire. Rubicon blanched at the thought of getting more; the only seam they had found near enough to the surface to be extractable was, unfortunately, only a hundred yards upwind of a tyrannosaur nest. He considered the few black rocks on the shovel, then tipped a third back onto the small pile. Darwin would just have to not exert himself today, while they considered their next move.

Arranged at Darwin’s stomach was the unwieldy yet vital furnace that kept him mobile and—though Rubicon was still mystified at the science behind it—alive. Beneath the aged botanist’s torn shirt, now more gray than white through lack of starch and washing, copper pipes and iron pistons snaked over his body in a dull metal matrix, bulky with pistons and shunts at his major joints. Darwin must have gotten up to relieve himself in the middle of the night, and the amazing yet grotesque external skeleton that ensured his longevity must have seized up, as it was doing more and more frequently in the past month. Arranging the meager lumps of coal on a bed of kindling and pages torn from the books they had managed to rescue from the wreck that had stranded them there six months ago, Rubicon struck a match and, when he was sure the kindling was catching, shut the little metal door to the furnace. Then he cast around for the oilcan and applied a few drops to the joints of the skeleton, still unable to stop himself from blanching as he saw the pipes that were sunk into the flesh at Darwin’s chest and at the base of his neck. The skeleton was the work of the eminent scientist Hermann Einstein, and it not only allowed the old man to move, albeit with a hissing, clanking, jerking motion, but also pumped his heart and did God knew what to his brain. Sometimes Rubicon wondered if he would ever understand the modern world, but looking out into the lush green jungle below, he wished beyond measure that he could see London again, its soaring spires, scientific mysteries, technological puzzles, and all.

As the furnace fired the tiny engines that powered the cage encasing Darwin’s emaciated body, the old botanist creaked into life, the metal jaw that was stitched to the bone beneath his bearded chin yawning wide. He flexed his ropelike muscles with an exhalation of steam from his joints and turned his milky eyes on Rubicon.

“Stanford,” he said softly. “I fear I cannot endure this purgatory another day.”

Rubicon patted him on the shoulder, the ridges of pipes and tubes warm now beneath his hand. He looked out across the jungle. “Not long now, Charles,” he said, though without conviction. “Help will come.”

From the journal of Charles Darwin, August ??, 1890

It is six months or thereabouts since the HMS Beagle II suffered its most woeful fate on the jagged rocks that lurk in the foaming seas around this lost world. Six months we have been stranded here, hidden from the outside world, barely surviving on our wits and hoping against hope to see the rescue mission that Professor Rubicon most wholeheartedly believes will arrive any day.

I confess that I do not share Rubicon’s faith in the power of the Empire to effect such a rescue. We are many thousands of miles from land, in uncharted waters, and within the sphere of influence of the Japanese. We had to steal here in secrecy, avoiding the shipping lanes and telling no one of our progress or destination. It took Rubicon half a lifetime to find his lost world, and now he believes that Britain will simply chance upon it? For all his bluster and rugged enthusiasm, I fear that Rubicon is merely humoring me. He knows that my survival for so long is a miracle in itself, and he wishes merely to jolly me along when he knows full well that we shall both die in this tropical nightmare. In idle moments—and is there any other kind in this place?—I wonder how I shall meet my inevitable death. What creature, I wonder, shall end my life? Will it be the snapping jaws of the tyrannosaurs? The horns of a triceratops? A brace of predatory velociraptors? It would be a fitting end for Charles Darwin, my detractors might say. Natural selection? Evolution? Mammals supplanting the dinosaurs? The old fool was eaten by that which he claimed gave way for the ascent of man!

Or shall I, as I almost did last night, merely wind down, let my furnace go cold through lack of fuel, and quietly switch off as Professor Einstein’s marvelous exoskeleton— surely both blessing and curse!—draws night’s veil over my eyes for the final time?

I am, as I have opined before, too old for this. I was a young man, barely in my twenties, when I voyaged to the Galápagos. Now I am approaching my ninety-second birthday, and only Einstein’s technology keeps me moving and living. I should never have let Rubicon talk me into this foolish venture. But the Professor of Adventure can be a persuasive chap, and even if he hadn’t plied me with brandy in the Empirical Geographic Club that cold January evening, I confess I would probably still have agreed to his madcap scheme. To think, a lost world where the dinosaurs still roam! The Cretaceous period, frozen in time, trapped in amber like the flies I found in the Galápagos! If I had one wish before dying, it would be to see my darling Emma again. How she would thrill to my stories. I do hope the children are taking good care of her.

Darwin closed the notebook and placed his pencil in the elasticized strap that held it together. They had salvaged little from the wreckage of the Beagle II, and had taken only what they could carry through the warren of labyrinthine tunnels that led from the stony beach to the interior of the extinct volcano that hid the lost world behind its soaring, jagged peaks. If they had known that a seaquake would cause a landslide that blocked their return to the shore they might have taken more supplies, or not ventured deep into the catacombs at all. But, as Darwin had already noted, Rubicon had a persuasive nature. The Professor of Adventure! The toast of London! And he had doomed them all.

Of the six survivors of the wreck, only Darwin and Rubicon remained. The majority of the crew of the Beagle II had been lost in the storm-tossed waves that crushed the ship as though it were merely a child’s toy in an overfilled bathtub. Rubicon had grasped Darwin’s collar and struck out for the dark shore with strong strokes. The morning that rose over the uncharted island had revealed the flotsam of the wreckage drifting toward the beach, and four others alive: two seamen, the first mate, and the cabin boy. One of the sailors had died beneath the landslide as they ran through the black tunnels to the salvation of the jungles within the caldera of this unnamed volcano. The first mate had been torn apart by two battling spinosauri as the dwindling party looked on in horror and amazement at their first sightings of the impossible lizards that still ruled this unknown corner of the Earth. The cabin boy had fallen to his death from the high crags, trying to climb toward the freedom he believed must be over the horizon. He called horribly for his mother all the way down to the far jungle below, where Rubicon later found his bones picked clean by predators. The final crewman had lasted until just the previous month, when hunger and madness possessed his brittle mind and he stripped naked and ran screaming into the towering flora, never to be seen again. His final, distant screams, choked by whichever beast had taken him in the shadows of the jungle, haunted Darwin still.

Rubicon approached the rock where Darwin sat in melancholy reflection, wiping himself dry with a piece of the first mate’s old coat. The professor was fastidiously clean, even in this abandoned hell, and he washed every morning in the cascade of water that ran from subterranean sources into a waterfall thirty feet below the lip of the cave. Rubicon was convinced that the salt waterfall must come from the outside sea, and he had formulated plans to follow the underground river through the impassable cliffs. But Darwin was not up to the journey and besides, Rubicon had not yet worked out how to pass through the raging torrent without drowning. Darwin wondered how long it would be before Rubicon abandoned him and sought freedom alone.

As Rubicon buttoned up the thick black cotton jumpsuit he always wore on his adventures and finger-combed his beard into a manageable style, picking out ticks and fleas and crushing them beneath his square fingernails, he nodded to the distant peaks.

“I think I shall go and light the beacons again today.”

Darwin nodded. Rubicon had spent days climbing as high as he could at each compass point of the caldera, assembling piles of dampened wood that smoked blackly and, he hoped, would attract the attention of passing ships or dirigibles. Not that they had seen even a hint of an airship since their incarceration; this corner of the Pacific was Japanese waters, but it seemed even they didn’t pass over at all. At first the survivors had been afraid of attracting the attention of the Edo regime, or the breakaway Californian Meiji, but now they did not care. To be rescued by anyone, even enemies of the British Empire, would be preferable to this. The government in London could at least try to parlay with the Japanese for their release, even if they were arrested on suspicion of spying; the dinosaurs would not enter into any kind of dialogue with Whitehall, Darwin thought wryly, even if the authorities knew where to find them.

“If you think it will do any good, Stanford,” said Darwin.

“I do,” said Rubicon. “When men like us give up hope, Charles, then the very Empire is lost. I shall be back before dark.”

Beneath the baking sun, Rubicon clambered swiftly up the eastern wall of the volcano, keen to reach the heights where the cooling breeze would dry the sweat pearling on his forehead. This was the least onerous of the climbs, apart from the final stretch of forty feet or so, which was a perilous vertical face with scant handholds, and he liked to tackle the eastern side first to limber up. That, and the unyielding sea beyond stretched toward the Americas; if there was any hope of rescue, it might well come from that direction. The Spaniards plied the waters between Mexico and the Californian Meiji, and the occasional airship from the British-controlled Eastern Seaboard sometimes shuttled between New York or Boston and the Spanish territories. But six months had passed with no sign of life elsewhere in the world; Rubicon tried to maintain a jolly, hopeful facade for Darwin but his own optimism was fading fast. If they were to die in this hellish lost land, he hoped that Darwin went first. He couldn’t bear the thought of the old botanist slowly winding down, trapped by his steamdriven exoskeleton and forced to watch, immobile, as death approached—either on the lingering tiptoes of starvation or with the snapping teeth of one of the beasts that roamed the island.

This lost world had been everything that Rubicon had dreamed of, everything he had devoted the last ten years to finding. But his ambition to bring the rude beasts from before the dawn of time to display in triumph at the London Zoo was dashed, as surely as he would be on the rocks below if he lost his footing negotiating the last segment of his climb. He allowed himself the fantasy of imagining that their mission had been a success, and that they had returned to London with the Beagle II’s hold groaning with breeding pairs of triceratops, pteranodons, ankylosauri, and even tyrannosaurs. He would have been the toast of the Empire. He briefly wondered what was being said of Darwin and himself now, how many column inches were being devoted in the London papers to their lost mission. Six months had passed… perhaps their names were barely mentioned anymore. The great explorers, missing in terra incognita. Presumed dead.

Rubicon hauled himself up onto the thin crest of the volcano’s lip, barely three feet wide before it plunged in a sheer, unscalable cliff to the angry surf that crashed on the jagged rocks far below. There was no way of descending and no beach or footing there if they did. Rubicon slung off his back the sticks and vines he had bound together with twine and assembled them in the ring of rocks he had prepared there many months ago, when he had first started lighting the bonfires. Matches saved from the wreckage were kept in a leather wallet beneath the largest rock of the makeshift fireplace; only a dozen were left here now. He lit one and shielded it with his hand, holding it to the dry moss at the base of the small beacon and blowing it gently until the flames fanned out and the kindling caught.

The greenery burned reluctantly, sending thick black smoke pirouetting into the unbroken blue sky. Rubicon nodded with satisfaction. Three more beacons to light, then perhaps he might scoot by that tyrannosaur nest and see if he could scavenge a few lumps of coal for Darwin’s furnace. Dusk was the safest time, when the beasts had eaten and lolled with full bellies around their nest—though “safety” in this place was a relative concept. He took a few sips of water from his canteen and prepared for the descent, scanning the horizon one last time with his hand shielding his eyes.

There was a ship.

Rubicon swore and rubbed his eyes. Surely it was a breaching whale, perhaps, or piece of driftwood. It was so very distant, merely a speck on the glittering blue waves. But as he peered and squinted he was sure he could make out an almost invisible thread of exhaust steam. It was a ship. And it was heading for the island, coming up from the south and the east.

Rubicon gathered up all the kindling and leaves he had and thrust them onto the bonfire, then turned and let himself over the edge. Slowly, slowly, he commanded. It would not do for you to fall to your death just as salvation is at hand.

“Charles! Charles!”

Darwin had been napping, and at the insistent calls from the unseen Rubicon he awoke sharply and stretched, his exoskeleton creaking and hissing at the joints. “Stanford?”

Darwin peered out beyond the lip of the cave. He could see the pillars of smoke from the eastern and southern walls of their prison, but not from the other walls. Had something terrible occurred to stop Rubicon lighting the other beacons? The professor, his face red from exertion, appeared over the ledge, clambering madly into the cave.

“Stanford? Are you quite well?”

“A ship, Charles! A ship! We are saved!”

Darwin pursed his lips. “You are quite sure? Not a mirage, or—?”

“Quite sure!” said Rubicon happily. “I saw it from the east and then again from the south. It is closing in at a fair lick.”

“British?” said Darwin, not daring to hope.

“I cannot tell,” said Rubicon, shaking his head. “But it could be the Flying Dutchman itself for all that I care! Come on. I calculate it is heading for the place where the Beagle II was lost. We must make our way there at once.”

Darwin frowned. “But the tunnels collapsed. And is that not close to the nest of those tyrannosaurs… ?”

Rubicon was filling his knapsack with their remaining dried meat and lumps of coal. “Pack just what you can carry,” he said. “We must away directly.”

Darwin nodded and tucked his journal into his own leather satchel. That was all he required: his notes, drawings, and observations of the fantastical flora and fauna on this lost island. Could it really be true? Was rescue really at hand?

Darwin staggered as the ground beneath his feet shook violently. He looked at Rubicon, who frowned and stared out to the jungle as another tremor rattled the cave.

“An earthquake?” asked Darwin.

Then there was another tremor, and another, and a column of smoke and dust rose from the mountainous caldera between the eastern and southern beacons. Rubicon shook his head. “No. A bombardment. They’re shelling the rock face.”

2

The Hero of the Effing Empire

Along one of the paths that Rubicon had cleared with stick and machete during their six-month incarceration on the island, the pair of them hurried toward the booming bombardment. The shelling had disturbed the island’s occupants; the long necks of brontosaurs peeped inquisitively above the tree line, and pterosaurs shrieked and wheeled on the thermals rising from the hot jungle. On the periphery of his vision, Darwin, beset by buzzing flies that nipped at the beads of sweat on his forehead, saw shapes flit between the trees and bushes: raptors, no doubt. The carnivores were sufficiently startled by this incursion of the modern world to put their hunger to one side for the moment and let the two humans pass unmolested. Rubicon grabbed Darwin’s arm and dragged him behind a thick tree trunk as three lumbering triceratops, their yellow eyes wide with uncomprehending panic, crossed the path and crashed into the jungle, flattening a copse of gigantic magnolia.

“We’re coming up to the tyrannosaur nest,” whispered Rubicon. “I suggest we give it a wide berth. I’m going to lead us through the undergrowth.”

Darwin nodded. His legs felt heavy and unresponsive, a sure sign that his exoskeleton was seizing up again. He needed coal for the furnace, water for the pumps, and oil for the joints, none of which was in handy supply. Should this rescue of Rubicon’s not occur, Darwin was suddenly sure that he would simply give up the ghost there and then. He could not bear this existence a moment longer.

They crept around the perimeter of the nest, a clearing in the forest that stank of ordure. Darwin could make out the shuffling shapes of the tyrannosaurs, disquieted by the bombardment but remaining fiercely territorial. Rubicon put a forefinger to his lips, met Darwin’s gaze with a look that said Don’t ruin it now, and led him quietly through the fig trees, palms, and unruly plane trees. Finally the nest was behind them and the trees thinned out to reveal the sheer rock face, the labyrinthine tunnels where the two men had entered the volcano lost beneath the mounds of massive rocks.

Another shell exploded on the far side of the wall, and there was a pregnant pause, then the rock face seemed to move like liquid, sliding in on itself and then rumbling down in an avalanche of huge boulders. Darwin and Rubicon stepped back to the jungle as the rock collapsed with a bellow, opening up a wedge of blue sky beyond. The wall was still sixty feet high, but Darwin could see the drifting steam of the ship that lay beyond, and he heard a roaring sound he at first thought was an attacking dinosaur… then realized was the first human voices apart from Rubicon’s he had heard in months. It was men, and they were cheering.

Rubicon broke free of their cover and began to clamber up the rocks, Darwin struggling behind him. Before they had gotten halfway up, three figures appeared from the other side, then a phalanx of sailors carrying rifles. Darwin felt tears begin to fall uncontrollably down his face.

There was a broad man with a beard, wearing a white shirt and with the bearing of a sea captain. Beside him was a younger man, thin and tall with dark curls cascading down his shoulders. The third was a corpulent, huffing, pasty-faced figure, frowning into the sunlight and coughing with displeasure.

“Professors Stanford Rubicon and Charles Darwin, I presume?” called the younger man as the sailor began to descend to help the pair. Darwin sank to his knees on the rocks, all his strength having deserted him.

Rubicon called back, “You are most correct, sir! To whom do we have the utmost pleasure of addressing?”

The young man gestured to his right. “This is Captain James Palmer, whose fine ship the Lady Jane has brought us to your aid. My companion is Mr. Aloysius Bent, a journalist currently attached to the periodical World Marvels & Wonders.”

Even as Darwin’s strength fled, Rubicon’s seemed to return with renewed vigor. He closed the gap and grasped the young man’s hands firmly. “And you, sir?”

The fat journalist who had been introduced as Bent spoke up. “This is Mr. Gideon Smith. He’s only the Hero of the effing Empire.”

“We are saved!” gasped Darwin, and collapsed in a faint on the piles of gently smoking rubble.

Darwin came to as one of the sailors put a canteen of glorious fresh water to his parched lips. He feared that when he opened his eyes it would all have been a dream, but there was Rubicon, talking to Captain Palmer, Mr. Smith, and Mr. Bent, as the crewmen with the rifles fanned out around them, their guns trained on the jungle.

“But how did you find us?” Rubicon was asking.

“A survivor from the wreck of the Beagle II,” said Palmer. “He drifted for many days, clinging to a piece of timber. He was picked up by a Japanese whaler and languished in a prison near Osaka, accused of spying, for four months. He was freed as part of a diplomatic exchange with the British government, and when he returned to England he was able to pinpoint the Beagle II’s last position, give or take a couple of hundred miles. We sailed out of Tijuana at the bidding of the Spanish government two weeks ago. If it hadn’t been for your beacon, I think we would have missed you completely.”

“And did you find your lost world before you were wrecked, Rubicon?” asked Bent.

Darwin sat up with some effort. “You are standing in it, sir.”

Gideon Smith looked around at the jungle rearing up before them. “You don’t mean… prehistoric beasts? Here?”

Rubicon nodded. “Such as you have never imagined, Mr. Smith. And half of ’em would have you for breakfast… some of ’em with one gulp!”

“But how did you survive?” asked Smith.

Darwin tapped his head. “With that which separates us from the monsters, sir. Intellect. Invention. The will to live. Survival of the fittest, you see.”

The fat one, Bent, surveyed the jungle. “These beasts…”

“All around us,” said Darwin. “Your ship is just over these rocks… ?”

Captain Palmer nodded. “Aye. We should be away.” He turned to address one of the sailors. “Mr. Wilson, please go back to the Lady Jane and have the mate prepare us for sailing.”

He turned to address Rubicon. “Sir, I understand your mission was to bring samples of these monsters back to London. I can tell you now that I will have no such business on my ship. We are here to rescue you, not transport a menagerie from under the noses of the Japanese.”

“Understood,” said Rubicon. He cast a glance back to the jungle. “Before we go… I would just like to collect something… .”

Darwin looked at him quizzically, but Rubicon promised he would be back within five minutes and jogged back into the dark trees.

“But how are they still alive, these dinosaurs?” asked Bent.

Darwin shook his head. “Whatever evolutionary occurrence or, perhaps, natural disaster that occurred toward the end of the Late Cretaceous epoch did not, seemingly, affect this island. It has remained untouched ever since, apart from the world, out of time. The creatures have thrived for more than sixty-five million years. It is a living museum!”

“And one we shan’t be returning to,” said Palmer, frowning. “We are right in Japanese waters here, gentlemen. If we get back to Tijuana without being seen it shall be a miracle. This could cause a major diplomatic incident.”

Smith looked at the jungle. “Where is Professor Rubicon?”

Darwin tried to stand but fell again as the earth shook. He looked at Captain Palmer. “Your bombardment continues?”

Palmer narrowed his eyes. “No…”

The ground shook again, and again. There was a shout and Rubicon broke through the trees, running as fast as he could, waving at them. “Go!” he yelled. “Get out of here!”

“What the eff…” said Bent, and then there was a roar that made Darwin feel as though his eardrums had burst. The trees behind Rubicon splintered like matches and from the dark greenery burst a fluid brown streak, all yellow eyes and teeth like kitchen knives.

“Oh Lord,” said Darwin. “A Tyrannosaurus rex!”

Smith and Palmer took hold of Darwin and hauled him up the rocks, as Bent scrabbled after them and Rubicon joined the climb. Darwin glanced at him but Rubicon kept his mind on scrambling over the blasted boulders as the seamen behind stood their ground and let loose a volley of bullets at the beast, forty feet from nose to whipping tail. It bent its head low and roared at them again. Darwin heard a scream, and Palmer cursed. He looked over his shoulder as they crested the boulders to see the beast shaking one of the sailors in its vast jaws.

“Pull back, men!” cried Palmer, leading them down the shale to a rowboat bobbing in the shallows. Ahead of them, anchored a hundred yards offshore, was the steamship the Lady Jane.

As they bundled into the rowboat, Darwin noticed the sunbleached, seawater-bloated timbers of the wreck of the Beagle II, still caught in the savage rocks that surrounded the island. There was another scream: another lost sailor. After a further volley of shots the remaining crewmen skidded down to the small beach and piled into the boat, immediately pulling on the oars to take the men, painfully slowly, away from the island.

Then the tyrannosaur loomed into the jagged gap between the high walls, its claws scrabbling for purchase on the loose boulders. It sniffed at the unfamiliarly salty air, swiveling its blazing eyes to fix upon the frantically rowing sailors. Its brown tail, crested with black, whipped back and forth as it seemed to consider the vast, oceanic world that lay beyond its hidden lair.

“We are safe,” said Darwin, as they closed half the gap to the Lady Jane. “I do not think the beasts can swim.”

Bent puffed alarmingly beside him. “You don’t think? Can’t you be surer than that, Darwin? What the eff is that thing, anyway?”

“I told you,” said Darwin. “Tyrannosaurus rex. The tyrant lizard. Dark master of the Cretaceous.” He paused and glanced at Rubicon. “I wonder what made it attack us like that. What alerted it to our presence?”

The beast remained on the beach, stalking up and down and staring out at the Lady Jane as the crew helped the men aboard. Rubicon graciously declined help with his satchel, which he kept close to him as he climbed onto the deck.

“We’ll make steam for Tijuana,” said Captain Palmer. “As far away from that thing as humanly possible. We’ll need to go swiftly and quietly, avoiding the shipping lanes until we get to Spanish-controlled waters.” He looked at Darwin and Rubicon. “I dare say you gentlemen would like a bath and some good food, and a soft bed to sleep in.”

Darwin began to weep. “I thought we would never be rescued. Thank you, kind sirs.”

Palmer nodded toward Gideon Smith. “He’s the one you want to thank. He’s led the mission. Like our Mr. Bent said, Mr. Smith’s the Hero of the Empire.”

“I thought that particular appellation belonged to Captain Lucian Trigger,” said Rubicon, “though I do not doubt that Mr. Smith is fully deserving of the title also.”

“A lot has happened in the six months you have been missing,” said Smith. “Let’s go to Captain Palmer’s quarters and I’ll fill you both in.”

“A favor, first, Captain,” said Rubicon. “Could I put my bag in the furnace room, do you think? There’s something in here that I would awfully like to keep warm.”

Palmer narrowed his eyes, then shrugged and had one of the sailors take Rubicon into the bowels of the Lady Jane. Rubicon dismissed the sailor with his profuse thanks, and when he was alone he gingerly took his satchel and placed it securely between two crates, up against the hot steam boiler. Before he departed he opened the leather flap and glanced inside. There was an egg, as big as a man’s head, mottled in purple and pale blue. Rubicon smiled and went to join the others for the promised food, bathing, and news, past the shadowy alcove where he failed to notice the figure of Aloysius Bent watching with interest.

As the ship began to disappear from view, she continued to stalk up and down the beach. She had been aware of them, of course, dimly, in her tiny brain. Creatures like none she had ever seen, like none that had ever lived in her world. They scurried around and hid in caves, nursing flames and harvesting fruits. They were food. Her mate had tasted one, many months ago, but the surviving two had always managed to evade her and her family.

But this was not about food. Food was plentiful, and were not she and her mate the rulers of all they surveyed? All they had surveyed, perhaps, until today. Until this jagged doorway was opened up and this strange, huge, wet world that stretched in all directions came into view. No, this was not about food.

This was about family.

Whatever they were, they were gone with others of their kind.

And they had stolen from her, stolen that which was most precious.

She raised her head to the dull sky and roared, and this time her roar was not reflected back at her by the rock walls of her home, but traveled out for who knew how long and how far? Out into infinity. Out where they had taken what was not theirs.

She dipped a claw into the lapping cold water and recoiled. She grunted, angry with herself. Then she stamped, hard, in the shallows, and left her huge foot there, in the water.

It wasn’t so bad.

Taking a step, and then another, she waded out until she could no longer feel the rocky ground. Panicking, she thrashed her tail and reached her head up to the sky, her useless forearms paddling frantically. She pumped her legs and felt herself move forward. Her forearms, perhaps not so useless after all, allowed her to keep her head out of the water. And her tail, as it thrashed, steered her course between the tall, cruel rocks.

Out to the open sea. Out to where those who had stolen her unborn baby had gone.

With the single-minded ferocity of a wronged mother, she howled at the sky again and began to claw her way through the water, heading, though she didn’t know it, south and east, in the all but dispersed wake of the Lady Jane.

Gideon Smith and the Brass Dragon © David Barnett, 2014